This story is part of Next Generation, a series in which we give young makers a platform to showcase their work. Would you like to see your work here? Get in touch and plot your coordinates as we navigate our future together.

Elissa Brunato is a recent graduate of the Material Futures program at Central Saint Martins, London. For her final project, she collaborated with material scientists Hjalmar Granberg and Tiffany Abitbol from the RISE research institute of Sweden, to create shimmering sequins made from an unexpected material: wood.

With experience working for both ready-to-wear and luxury haute couture fashion houses, Brunato has witnessed first-hand the disjointed and damaging processes of the fashion industry. Indeed, around 50,000 tons of dye are discharged into global water systems per year, and hidden behind the joy vivid colors may bring to consumers, uneven and exploitative supply chains often prevail. Additionally, sustainable materials for embroidery in particular are extremely limited; they often contain microplastics, and by now we are well aware of the devastating impact of such materials on our ecosystems. Meeting this urgency, the designer sought to find a sustainable solution to meet our love for shimmer.

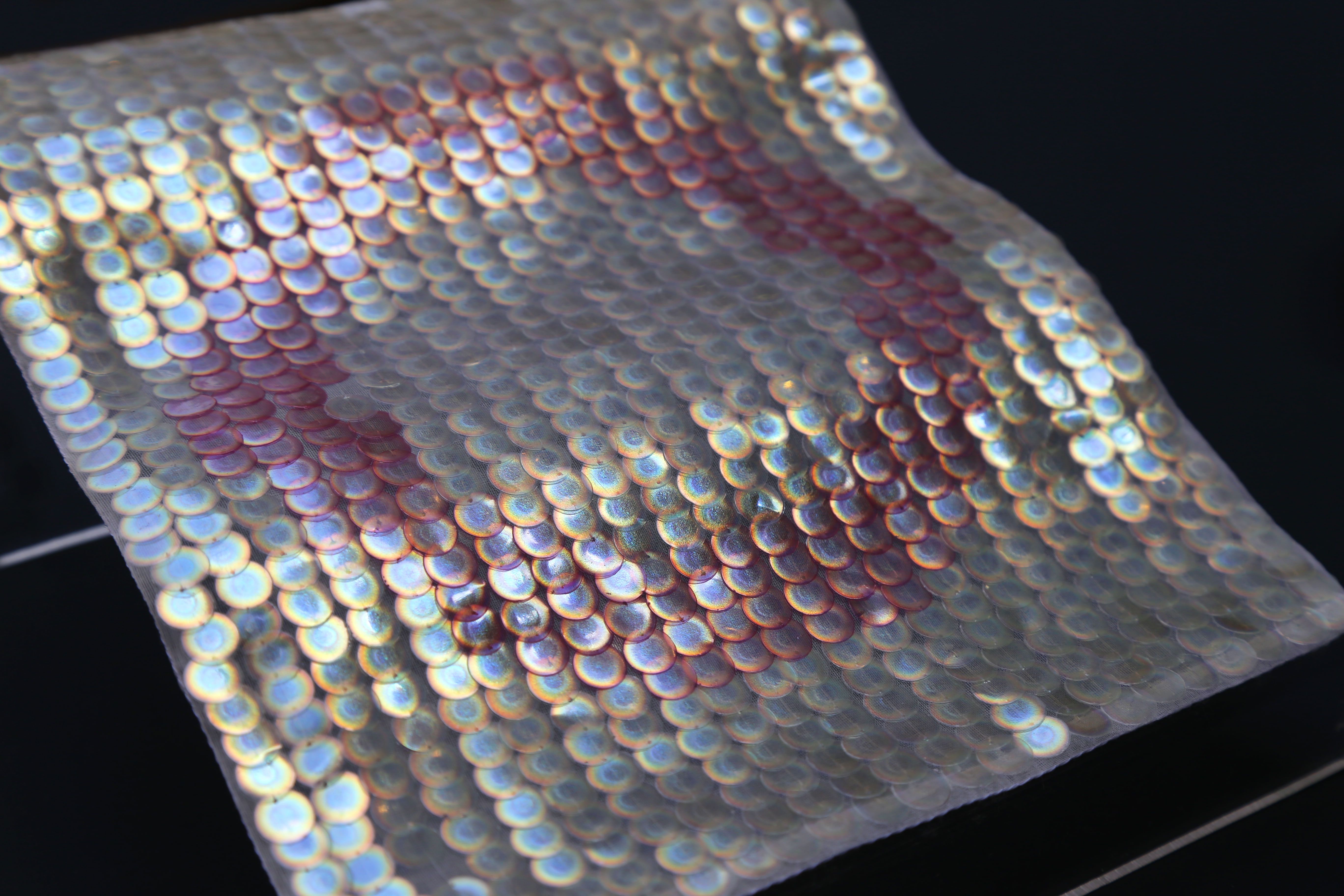

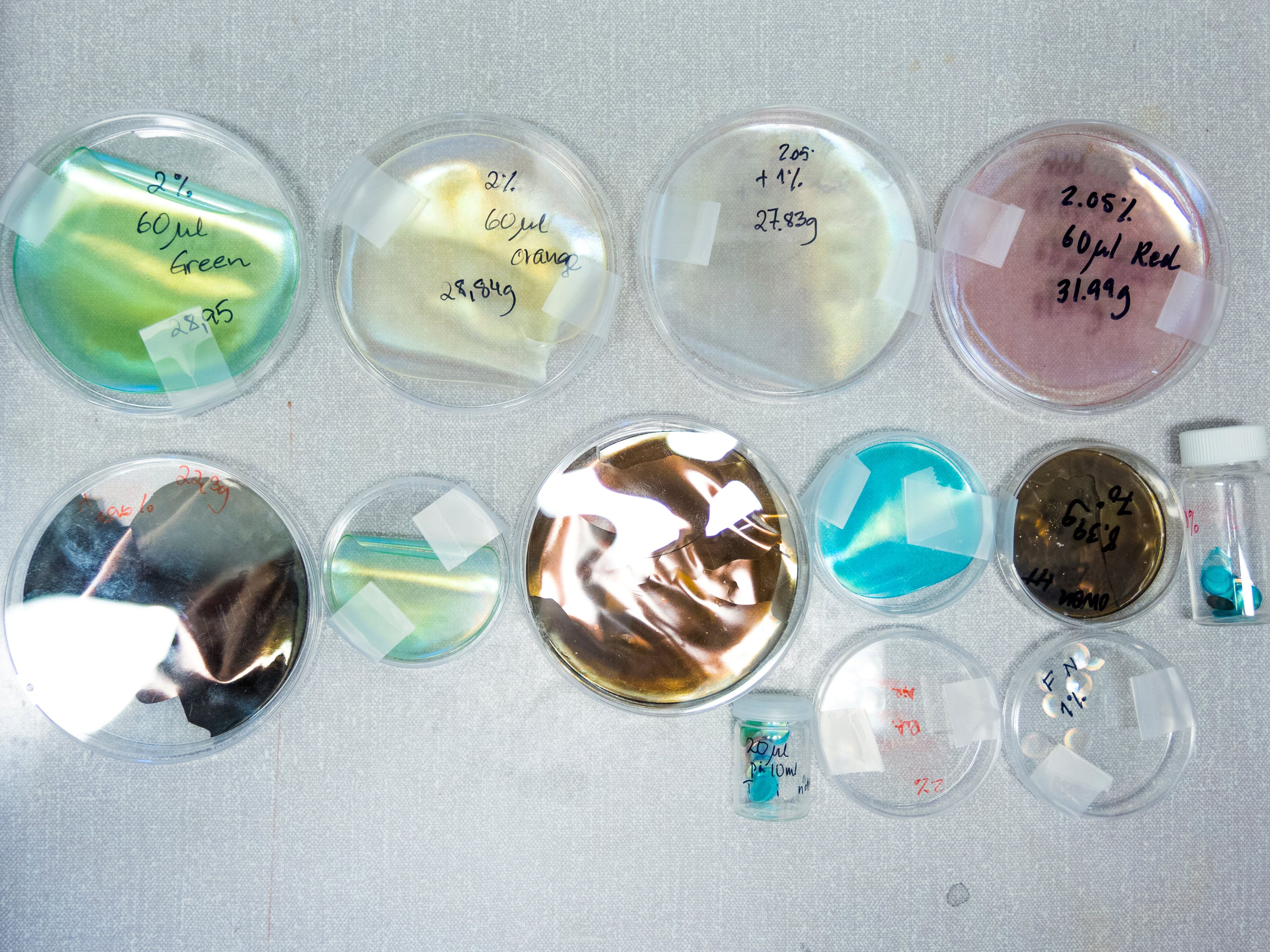

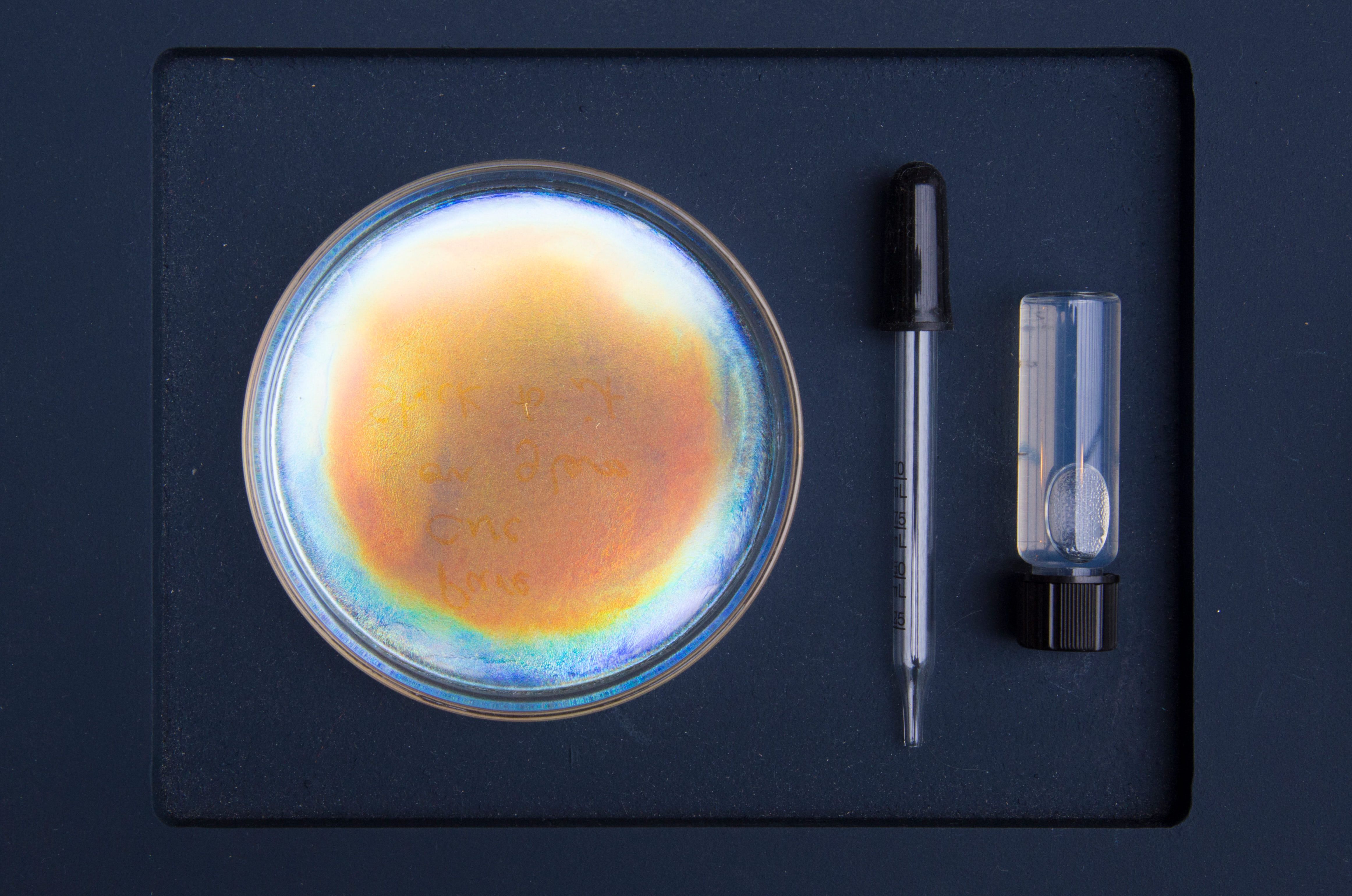

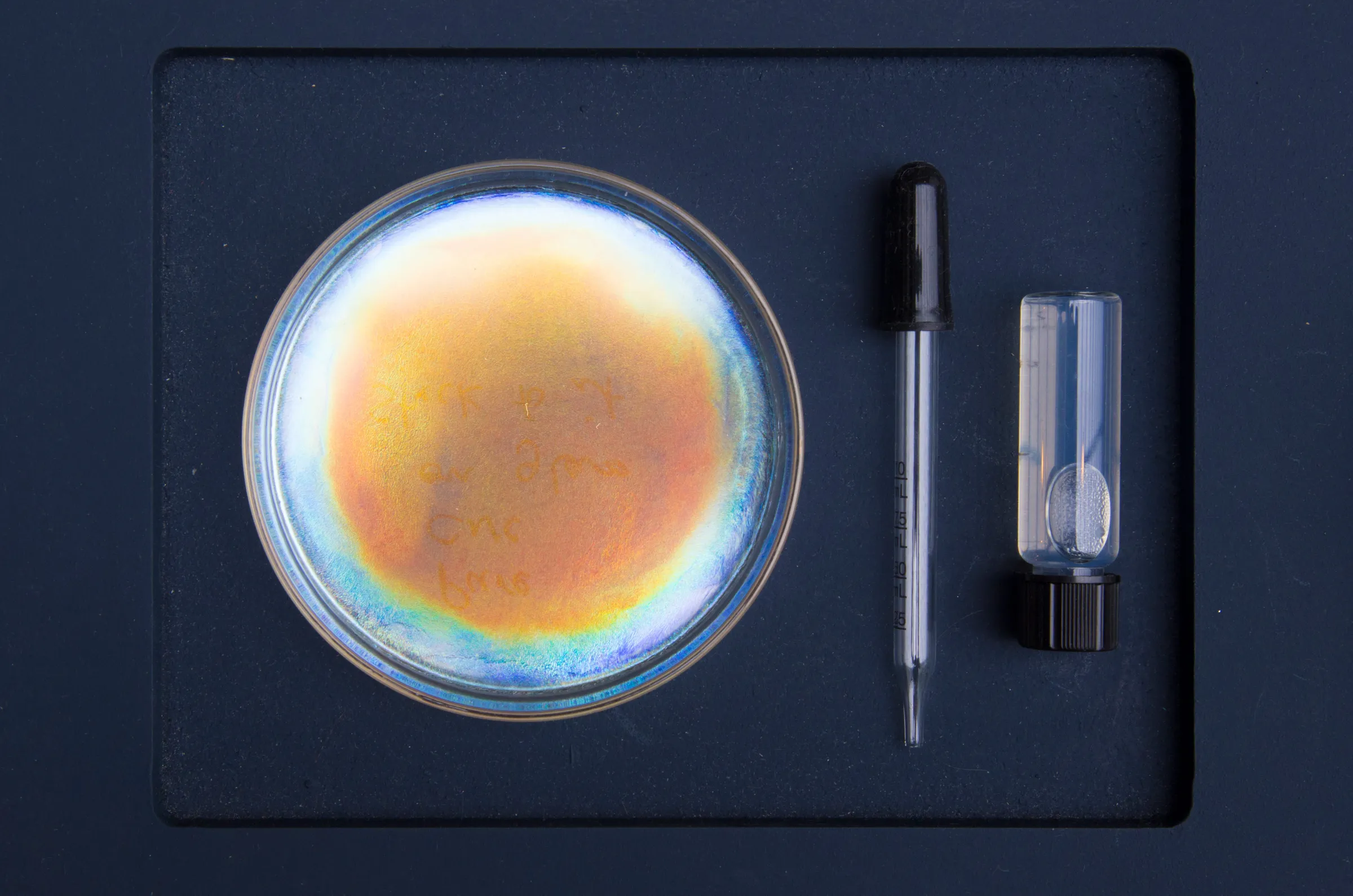

Wondering how the sequins are made? Brunato and her collaborators at RISE have been working with biotechnologies that made it possible to harness cellulose’s natural ability to interact with light. By extracting crystalline from cellulose, wood-originating matter can imitate the alluring aesthetics of shimmering structural colors found in nature, as seen in peacock feathers and beetle wings. The result is a game changer: a durable, compostible sequin made from natural materials, with a shimmer achieved using nature's technique of structural color.

We found out more about the Bio Iridescent Sequin...

Why make a sequin?

Brunato’s research reveals how sequins tell the story of an age-old “human desire to attain nature’s beauty,” and that “our attraction to glimmering surfaces might even relate back to our primary need for water.” Charting the history of sequins, she notes how they are “deeply interwoven with the cultures in which they exist.” For example, sequins have appeared on the burial garments of Egyptian royals in the form of metal coins, and have adorned the dresses of 19th century nobility in the form of beetle wings.

"While the democratization of the sequin has been positive, the increased use of petroleum has been creating environmental problems."

Today, plastic is the new preference, and mass-produced sequins can be found in every fast-fashion store. Brunato recognizes that “while the democratization of the sequin has been positive, the increased use of petroleum has been creating environmental problems.” However, rather than rejecting this form of decoration altogether, Brunato began her quest to find an environmentally conscious approach to our historic fascination with shimmer.

Nature meets technology

So, how to resolve the conflict of attaining nature’s beauty without harming it? For Brunato, “nature provided the clues.” The designer is inspired by how the nonhuman world is “abundant with examples that demonstrate the dazzling optics of structural colour.” Indeed, pollia berries, bacteria strains and beetle wings all gain their vivid colours from microscopically small nano-structures that interfere with visible light.

"we are part of nature, and technology should become our means to shift our relationship with it."

When it comes to incorporating nature’s techniques into a material application, Brunato sees technology as an essential tool for “re-imagining the landscape of available materials.” She further insists that “we are part of nature, and technology should become our means to shift our relationship with it...we are at a point where biotechnologies can enable us to reshape manufacturing.”

Additionally, as a result of scientific exploration, Brunato explains how “we understand genes, growth and forming so much better than before. We can look into materials on a molecular level and change their behavior.” Certainly, the scientific expertise of her collaborators were essential for shifting the Bio Iridescent Sequin from ideation to a material application: “the collaboration really lifted the project to the level that I imagined, by connecting to other experts, we could lift my idea from being a concept to being a reality,” says the designer.

The Nature of Collaboration

We spoke to the Bio Iridescent team to find out more about the nature of collaboration. From a design perspective, Brunato shares that “the challenge lies in learning other disciplinary ‘languages’, understanding each other’s viewpoints, approaches and interests. However, it happened very organically in this case.”

Tiffany Abitbol, a PhD chemist that specializes in cellulose and nano-materials, highlights the true compatibility of design and science: “scientists and designers have a lot more in common than they may realize. We are creative and driven problem-solvers, interested in the process as much as the final result.” She also adds that “as the issue of sustainability impacts all humans, I think a representative, multi-disciplinary and collaborative group is essential to bring forward real solutions.”

"Scientists and designers have a lot more in common than they may realize. We are creative and driven problem-solvers."

Hjalmar Granberg, who since obtaining his PhD has worked on creating new bio-based materials, notes how “feedback and new ideas from a design perspective is valuable, and it increases interest in the field of wood-based decoration and aesthetics.” Additionally, he experienced that “new questions and new perspectives arise simultaneously in such collaborations.” For example, Brunato’s insight helped the team overcome the issue of “how to present the results in a way that is attractive beyond a scientific context.”

The Future of the Bio Iridescent Sequin

All members of the team are highly optimistic about the future of the Bio Iridescent Sequin: “we could develop a process to manufacture the sequins on a larger scale, and I think we can also overcome challenges relating to their commercialization. I anticipate textile applications of nano-cellulose in the near future,” says Abitbol.

According to Brunato, the sequin has the potential to inspire a “shift of the fashion industry’s dependence on hazardous chemicals, petroleum and synthetic colourants.” She also sees the Bio Iridescent Sequin as a powerful precedent for the development of “more environmentally healthy alternatives” in the fashion industry.

"A powerful network of voices are re-envisioning a new manufacturing landscape."

Perhaps most importantly, the Bio Iridescent Sequin exemplifies how collaboration is crucial for realigning material processes to meet the needs of the planet. By producing a visually stunning and compostable alternative, the team have signalled a new approach to sustainable shimmering colour, and a waste-free alternative for micro plastics in the fashion industry.

The designer’s final message is this: “we have to link knowledge between disciplines and co-engage more intently to replenish our ecosystems.” Brunato sees today’s design climate as an “exciting time” where “a powerful network of voices are re-envisioning a new manufacturing landscape that links more closely to the ecosystem we are part of.”

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!