Why, despite hyperloops, e-bikes and self-driving cars, we still travel an average of 90 minutes a day — and what that says about our nature and our future.

Whether we set off on foot, hitch up a horse, or hop into a self-driving solar car, our modes of transport evolve at breakneck speed. But one thing has remained remarkably constant for thousands of years: we spend an average of 60 to 90 minutes a day on the move.

From prehistoric times through ancient Rome to the present day, humans seem biologically programmed to spend about an hour and a half in motion daily. Not because we must, but because we can.

This consistent travel time was first noted in 1977 by Dutch researcher Geert Hupkes and became known as the Brever Law. His insight has since been confirmed by global studies: whether you live in Tokyo, New York or Amsterdam — rich or poor — people spend roughly the same amount of time on the move. Only the distance changes.

Because when we can travel faster, we don’t get home earlier — we simply go farther.

The Faster We Travel, the Farther We Live

Mobility innovation doesn’t mean we travel less — it means our world gets bigger. What used to take a day’s journey can now be done in an hour. So we move farther from work, leave our parents’ village behind, and shop in distant cities.

Transport reshapes our cities. Ancient Rome stretched about five kilometers across — the distance a person can comfortably walk in an hour. The city’s scale was literally aligned with the human body.

Car-based cities like Los Angeles are the opposite. The metro area now sprawls across more than 100 kilometers. In the early days of the car, this was ideal: you could drive anywhere quickly. But today, traffic jams are the norm and mobility is unpredictable. A city designed for freedom of movement now struggles with standstill.

A maglev train will soon take you from Osaka to Tokyo in 45 minutes. Elon Musk envisions a hyperloop that links San Francisco to Los Angeles in half an hour. The result? The merging of megacities. The Brever Law is having spatial consequences.

Blurring Boundaries — But Not for Everyone

This expanding travel radius has its downsides. More distance means more energy consumption, more CO₂ emissions — and more inequality.

Those without access to a car or fast public transport risk becoming isolated. The village bakery disappears because everyone drives to the big supermarket further away. The jet set flies to Paris for a shopping spree, while others struggle to reach a job or internship in the city.

At the same time, smart alternatives offer new opportunities to make mobility more equitable and efficient. The rise of the e-bike increases cyclists' range from 5 to 15 or even 25 kilometers — without needing a car. This doesn’t just change how we travel, but also the scale at which we live and work. Suddenly, a village 20 kilometers from the city becomes a realistic place to live.

Mobility expert Carlo van de Weijer therefore advocates for a bike metro network: a system of wide, separated, conflict-free cycling routes that connect urban areas efficiently. Investing in this kind of infrastructure makes cycling more attractive than driving for mid-range trips — with positive effects for public space, health, and access.

Mobility can connect — but it can also exclude.

Frictionless Travel

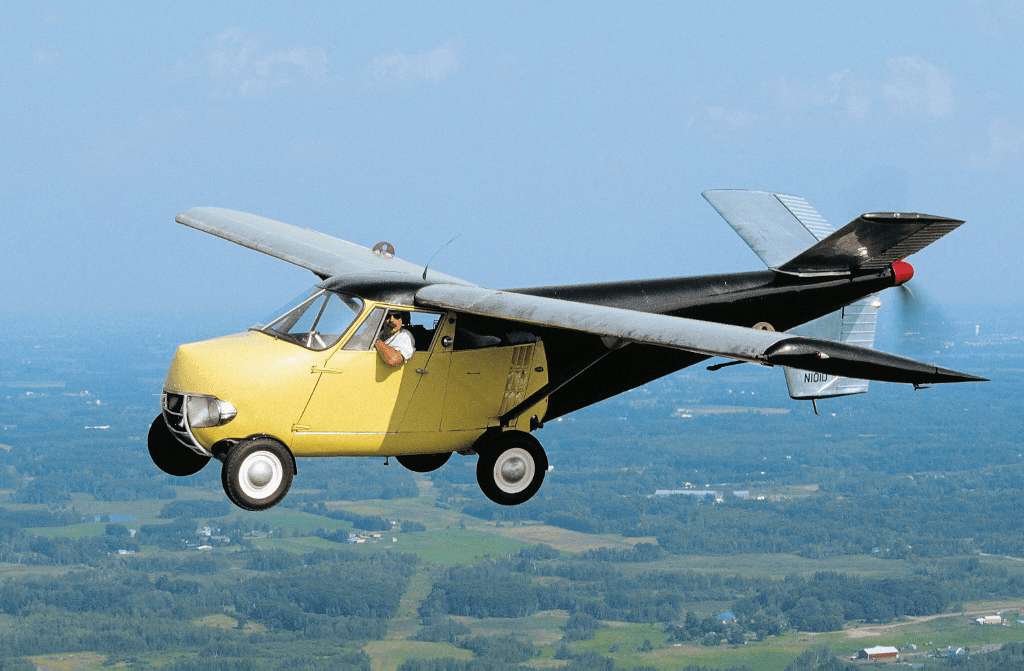

Something fundamental is shifting: travel is becoming less and less like “travel.” Where we once walked, jolted in carriages or bumped along rough roads, we now relax, work, or sleep on the go.

Trains, buses and airplanes increasingly offer tools to work, play games, relax or communicate with loved ones. The journey no longer interrupts the day — it becomes part of it.

Belgian supermarket chain Colruyt even introduced an office bus in which employees from Ghent begin their workday en route to headquarters. Twenty-eight workstations, Wi-Fi, great coffee. The commute disappears — the time becomes directly useful.

The New Nomad

What does this mean for our future? If travel is no longer a burden, if movement doesn’t “cost” us time, the Brever Law may soon be outdated.

We are becoming both settled and nomadic. Our homes stay in one place, but our lives unfold across multiple locations. Work, meals, meetings — they all happen on the move. So why would we still stop at ninety minutes?

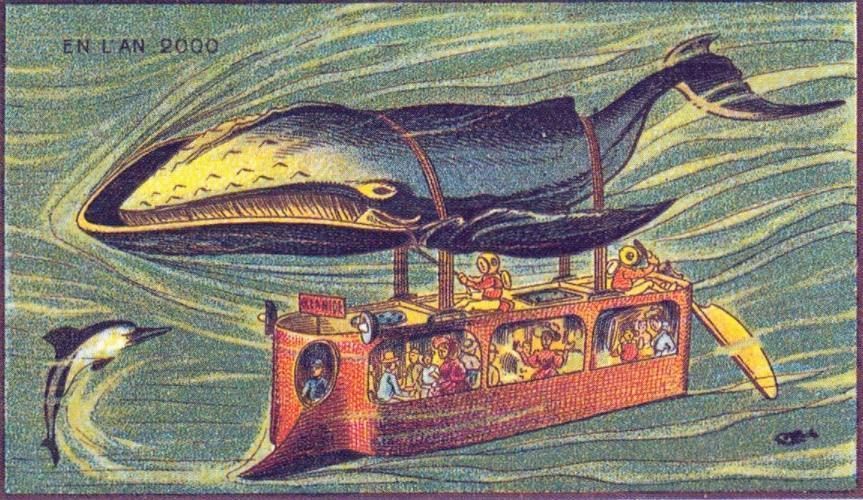

In the distant future, when we travel to other planets, journeys might take longer than a human lifetime. We may one day live in advanced spacecraft — in transit as a way of life. But the urge remains the same: the human desire to move, to explore, to find out whether the grass is greener on the other side of the hill.

Our vehicles are getting faster. But will our travel time stay the same — or not? Perhaps we’re on the brink of a mobility revolution in which meaning, not distance, becomes the new standard.

And maybe we’ll no longer travel because we have to get somewhere, but simply because we want to be in motion.

The journey as desire.

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!