In configuring our next nature, artists and scientists explore new languages that move beyond the Anthropocene - the era of human beings. These semantics would bridge the gap between mankind and technology, but also between humans and other species, establishing a cosmological understanding of life. Within this endeavour, bio-artists Amanda Baum and Rose Leahy delved into more-than-human narratives by creating a monument for the Microbiocene: the age of the microbial.

The Microbiocene is an epoch we’ve always lived in and will continue to live in, as the vibrant matter on planet earth emerged and thrives through microbial life, e.g. bacteria. In collaboration with the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), Baum & Leahy dove into the deep time of the microfossil molecules Emiliania huxleyi, which are found in ancient sea sediment. The result is an award winning symbiosis between art and science, as well as an artefact for the ecologies that are yet to be embraced by the human species.

We caught up with the duo and spoke about the philosophical matter pushing their piece to emerge, and the microbial matter it is made of.

"The installation envisions a future archaeological site, thousands of years from now."

You created the ‘Microbiocene’ piece for the Bio Art and Design Award last year. Tell us about the creative process of the project; did you already have in mind this result or did it evolve from something completely different?

The Microbiocene as an overarching concept is something we’d been thinking about for awhile - over the past couple of years almost all our projects have become about mapping out the Microbiocene - the ancient, ongoing, and future era of microorganisms. We’ve explored this through various lenses; spiritual, material, ritualistic, ancestral.

When applying to the BAD Awards, we were immediately inspired by the research from the Department of Marine Microbiology and Biogeochemistry at The Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). The scientists at NIOZ work with sea sediment containing microbial fossil molecules, which hold information about past environmental conditions, both recent and ancient.

NIOZ’s research combined with this cultural, philosophical framework gave birth to the idea of creating a form of ‘biological Rosetta Stone’ - a relic being found, and a language translated, to discover information about an ancient (invisible) civilisation.

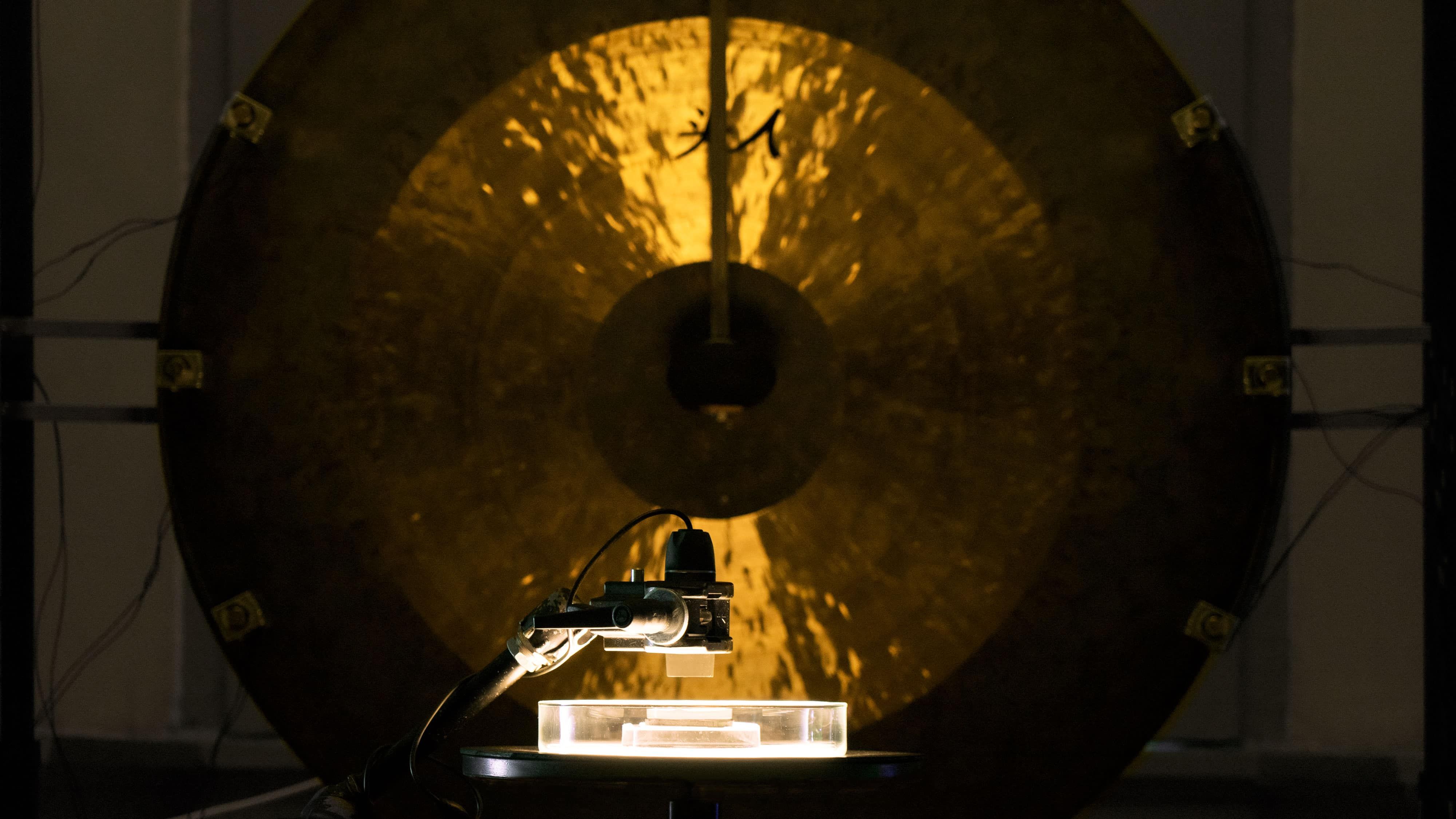

Inspired by the aspect of deep time, the installation envisions a future archaeological site, thousands of years into the future, where the Microbiocene monument is being found. It is inscribed with myths of the Microbiocene, a (re)telling of history and future on Earth as microbe-centric. These stories were based on information we unearthed from microbial fossils in sea sediment dating from the present to nearly 10,000 years ago. We then developed this data into narratives with our collaborating scientists, projecting different future scenarios.

The idea was to create a narration that was informed both by microbe and mammal.

You used ‘microglyphs’ in your piece —a microbe-centric language system co-created by the artists and scientists— how did you develop this language? Are the shapes imprinted on your works also literally found under the microscope?

The microglyphs were created with input from both scientific, cultural associations as well as free associations between us and the scientists. Some of the symbols are more literal —like a double bond in a molecule meaning cold, or Ehux being a graphic representation of how it looks, whilst some are more complex like the Microbiocene microglyph, which refers to life beginning on earth.

Whilst creating the microglyphs we discussed the multitude of forms that language takes,and the inherent human desire to traverse their boundaries – across cultures, disciplines and species. From the Rosetta Stone to art-sci collaborations to alien communication attempts, the wish to understand, and to translate is constant: we all dream of babel fish.

By creating a visual language for the Microbiocene, we attempted to move towards a more multimodal form of communication with the potential to be interpreted in various ways by anyone encountering it. Each of the microglyphs has multiple meanings, which change responsively with the surrounding microglyphs. Different compositions of the microglyphs explore movements within the meaning of the sentences.

The microglyphs are an initial iteration into working with the materiality of language, which we continue to explore in workshops, and our other projects. By consciously molding language, or sign making, into new biologically informed structures, we begin to weave our mammalian minds into the Microbiocene.

What kind of scientists did you collaborate with?

We collaborated with biogeochemists from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research – Julie Lattaud, Gabriella Weiss and Laura Schreuder. They study the alkenone biomarkers, especially sturdy molecules, left by microorganisms in sea sediment. This sediment is collected in long cores, which have a cross section of earth from the seabed and below, with the top layer being the most recent, and the bottom being from the mostpast.

"We like to work with scientists as partners on an equal basis of passion for understanding."

Their lab work is wonderfully intimate with the sediment that is collected. The coresare opened from a long tube and these incredibly distinct lines are revealed along the earth core, indicating thousands of years of life being lived before turning to matter.

Do you think you could have created this piece without this collaboration? What role does and should science play in art? Where does science stop and art begin?

The idea of the piece itself grew out of and was continuously informed by the scientific research, so it would have been another piece without the scientific collaboration. Like any other relationship, the symbiosis between art and science can and should take many forms, from the abstract and experimental to the more systematic.

At this point in time, we see not only creative potential but also a certain urgency, in the point between ecological transformation, emerging technologies and increased sensitivity and awareness towards the planetary web of life.

We like to work with scientists as partners on an equal basis of passion for understanding, working with and caring for living systems - although with very different means of research and expression. Before restricting ourselves within established epistemological systems, we try and create a nurturing space of shared curiosity, where ideas and visions aren’t limited to our individual areas of expertise.

Do you think that art is stuck in the anthropocene? Is art too much focused on human experience?

We think it’s important that art happens across many ‘cenes’- and that it’s also urgently important to reflect on our lives in the Anthropocene. Yet we are interested in exploring an alternative - one that is generative, slimey and messy, and optimistic about the adaptable forces of life. Microbiocene is just one. We continuously draw on inspiration from Donna Haraway’s ‘chthulucene’. Nurturing the diversity and moving away from dominant narratives of the Anthropocene is what we find urgently needed - within all fields, not just artistic.

Whilst creating Microbiocene we were thinking a lot about the magnitude of microbial experience that has come before us, and how this has had slow yet defining atmospheric and evolutionary impacts on the Earth, setting out the conditions for terran life to thrive. In contrast, human’s time on Earth is becoming very much defined by rapid changes, caused by a few, and resulting in wider impacts for all, and some much more than others. We believe a more microbial approach could trigger the emergence of new systems of adaptation and cohabitation.

"The monument is raised to mark and celebrate how humans learn to become more microbial in their planetary impact."

By looking at the history of time on Earth through the perspective of the Microbiocene, we hoped to condense this microbial evolutionary perspective into a material and sensorial experience able to inspire new ideas and trajectories challenging current anthropocentric worldviews. The Microbiocene monument is raised to mark and celebrate how humans learn to become more microbial in their planetary impact. Focusing on more-than-human adaptive strategies and experience as a worthy alternative. For us, drawing the narrative out of information in the material remains of microbial experience was a way to do this.

What role does materiality play in your piece and how do you elevate a materiality from human to more-than-human?

It was an incredible opportunity for us to use the sea sediment from our studies as part of the material in the sculpture.

The particular sediment we were working with is called calcareous ooze, meaning it contains a large proportion of skeletal remains of coccolithophores. This included Emiliania Huxleyi (Ehux) - the microorganism we were studying within the sediment - which has an incredible, vibrant materiality to it.

It is a single celled alga covered in calcium carbonate-rich platelets, which – with the help of deep time –transmutates into materials such as chalk and lime. The build up of these microscopic organisms on the seabed over long periods has an immense, macroscopic effect, as expressed in the White Cliffs of Dover and Møns Klint.

When understood as the material result of numerous coccolithophore bodies and existence, this coastal landscape becomes a more-than-human monument in itself. We wished to translate the immensity of this deep time within this lively material we had in the lab.

"Microbes are in a way a ‘gateway’ to the unknowns of the universe."

Part of what we find fascinating about the microbial world is the (to us) mysterious material liminality - microbes are in a way a ‘gateway’ to the unknowns of the universe, which we know makes up more than 90% of our perceived reality.

We can’t see the microbes with our naked eye, yet with electron microscopy technologies etc it’s revealed how alive, vibrant and ‘material’ they are. We see them as active, reproductive, communicative, busy organisms, just like ourselves.

This many faceted relationship between the microbes’ ubiquitous, ghostly presence and the very material reality of their lives, which resonates with our human experience, continues to puzzle and inspire us.

Even more incomprehensible invisible organic elements like bacteriophages, proteins, DNA, molecules, atoms, dark matter, down to the strange world of quantum mechanics, seems more ‘approachable’ when we think of them through the universal, microbial gateway.

Philosopher Timothy Morton wrote that we have to think in terms of durations, meaning we have to create a ‘deep time’ to ‘think ecologically’. Are you perceiving the world differently in terms of temporality since you made this work? Do you experience a more cosmological time as opposed to a human history?

When working with material such as the sediment cores that have such an evident history, it’s impossible not to become incredibly aware of and sensitive to the vast periods of time on Earth that have preceded us.

Our collaborating scientists work with these kind of time scales everyday, and so are used to thinking about time on Earth in terms of epochs, rather than through the length of their own human experience.

This was intriguing for us, and something we were trying to approach in Microbiocene not only as an installation, but also as a framework. Indeed, we believe that if humans could enter a mindset of deep time, we would see a big shift in our ways of producing and distributing materials. If humans could think in terms of the length of time that that plastic bottle will be on Earth, rather than the length of time it was experienced it in our lives, we surely wouldn’t be producing and distributing them in this way.

Yet, whilst the Microbiocene entails this very cosmological way of thinking – we’re not sure we can claim to have transcended into everyday cosmological experience of time from this. Despite our best efforts, we’re still just too darn human for that.

You both have a background in design - do you think different aesthetics in our everyday surroundings will amount to different environmental awareness? And if so, what’s the potential role of aesthetics in environment awareness?

In our work, we combine tactile, sensorial materiality with collective, ceremonial practicessuch as meditation, ritual and writing to practice and nurture a symbiosis between matter (microbial, mammalien, etc) and mind. We aim to bring focus to how internal and external realities are interrelational and constantly shaping each other. By materialising a speculative scenario, ongoing tendencies can be harnessed and the actual long term realisations can emerge.

We have both been inspired by biophilic design principles, how biomorphic form, aesthetic,and material can be used to strengthen, encourage, and practice our connection with other species and ecologies.

Recently we’ve been thinking about ‘microbiophilia’, and how to stir emotions for organisms we can’t see, yet live all around, on, and within us. In previous pieces such as Cellular Sanctum (2018), and The Red Nature of Mammalga (in collaboration with Naja Ankarfeldt, 2018), we created tactile biomorphic, microbial forms, microbial drinks, and written participatory chants, to create a tactile and sensual experience.

Through these aesthetic experiences we aim to seed a heightened awareness to the parallel microscopic world, within those who experience them.

More microbiocene ?

Cover photo by Max Kneefel.

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!