As a young bio designer at the start of your career, you'll have to overtake all kinds of obstacles. From the collection of living materials to working in a laboratory and collaborating with scientists; bio design is a newly emerging field in which you have to pave your own paths.

Meet biodesigner Emma van der Leest. Characterized by a DIY mentality, her multidisciplinary practice combines craft, scientific research and new bio-based production techniques.

Besides her own design practice, Emma founded an open-access wet lab and teaches at the Willem de Kooning Academy and the Design Academy Eindhoven. She welcomed us at the BlueCity Lab to talk about the emerging craft of biodesign, the importance of collaboration and experimental education.

The unpaved path towards bio design

Emma was schooled as a product designer at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. During her studies, Bio fabrication sparked her interest when she encountered the work of bio designer Suzanne Lee. Encouraged by a video explanation of Lee’s work, she bought Kombucha tea at a local shop and started experimenting at home. Back in her student dorm - to annoyance of her roommates that complained about the smell - she successfully grew cellulose out of it. This hands-on approach is what would characterize Emma’s work.

“By the time I had to choose an internship, there was only one place I wanted to go to, this was Suzanne Lee’s Biocouture studio in London. I landed an internship at her studio and this was kind of life changing for me: Here I learned to grow something in a ‘proper’ way”.

After Emma’s internship, she continued to work on her own bio-based design projects, but found difficulties in getting access to a laboratory.

Form follows organism

For her graduation project Form follows Organism in 2015, Emma developed a design methodology using a slime mold. “It was difficult to explain to people that I wasn't really designing a chair or a lamp, but that I was using an organism as a design tool. My entire school career, I firmly believed in the added value of developing materials and getting the most out of it by researching its properties, rather than just designing the next chair. We have to reinvent materials instead of reinventing products.”

We have to reinvent materials instead of products.

She also researched the changing role of the designer when working with living materials. “It is a completely different field, you have to develop a certain language to communicate with scientists.” She met with scientists who were doing great work, but didn’t apply their findings after publication. “And that triggered me - how many treasures are just laying in a lab that we can take out? As designers and artists, we hold the ability to visualize this research into tangible products.”

But, if form actually follows organism, how much influence does the designer hold? Emma explains that the laboratory is especially an area of control, because you decide upon the environment, the temperature and the nutrition of the material. She describes it as “a whole new craft that you need to develop.”

Both designers and scientists are skilled in working with specific materials and tools. Sharing this expertise is necessary to master the craft of bio design.

Currently, Emma is collaborating with a scientist from Leiden University to develop a coating for bacterial leather, as the bacterial leather itself is not water-repellent and not very flexible. “I'm quite excited to develop this. We started out with small experiments and now we are going to see how far we can take it. After all, I'm still a product designer and not a biologist.”

The blue economy

Her vision on bio design and the lack of available laboratories for young bio designers eventually led her to set up a bio lab at BlueCity in 2016. Located in an abandoned tropical swimming pool, BlueCity is the entrepreneurial hub for the ‘blue economy’ in Rotterdam — and the perfect environment for innovation.

The blue economy, a concept by author Gunter Pauli, is built upon businesses that involve waste as a new source, as the output of one entrepreneur serves as the input for another. Similar to nature’s cycles, the blue economy is based on networks.

“We try to work as an ecosystem, and really have nature sitting next to us at the table to learn how we can integrate her in different types of processes. If we want to shift towards a more sustainable blue and bio-fabricated future, we need to collaborate with nature — instead of working against her,” Emma says.

We need to collaborate with nature — instead of working against her.

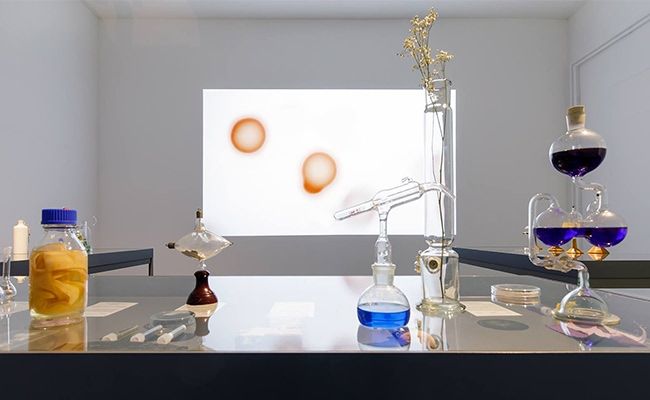

The Lab is the ultimate place to practice what they preach. “We need to stop talking about it and just do it. The Lab is really a place and the platform where people come to acquire experience and meet each other.” The old locker rooms of the swimming pool have been transformed into a workplace for designers, scientists, researchers and students that want to experiment with biology. It combines a wet lab and a dry lab, which allows users to combine different crafts to develop a final product.

Though the Lab is still a work-in-progress, Emma aims to provide all that she was missing during her own exploration of bio design: an open and accessible place to experiment, learn and collaborate. “I started Blue City Lab to lower the threshold for anyone who wants to practice biotechnology in a DIY way of doing it.”

Microbial Vending Machine

This ideology of open access also becomes visible in Emma’s latest project: the Microbial Vending Machine. For this project she took a FEBO vending machine – a characteristic Dutch vending machine which sells deep-fried snacks ‘from the wall’– and turned it into a shopping window for living materials and speculative bio products.

“This is to show people that in less than 10 years, taking an organism out of the wall will be as easy as it is to get a soda from a vending machine today.” And the accessibility of biomaterials such as algae, fungi and bacteria is essential for bio design and biotechnology to thrive. “These collectable organisms may be far more valuable in the near future than any candy bar or soda. Ultimately, the organisms enable us to approach design, science and construction in an entirely new fashion.”

Organisms enable us to approach design, science and construction in an entirely new fashion.

Emma points out that these fast developments and the endless range of possibilities may scare people, and sometimes it scares even herself. “We can now grow meat and textiles in the laboratory, and we are already able to grow bricks in order to build houses. So, what can't we grow?”

Yet, fear of biotechnology mostly comes from a lack of knowledge and understanding. “People may have heard about it, but don't exactly know what it is.” Therefore bringing the subject of biotechnology closer to the people may change the attitude towards it.

On the future of (bio) design education

Wrapping up our conversation, we asked Emma how she envisions an ideal future for experimental and bio design, and how we can overcome the struggles that she ran into in exploring the uncharted territories of bio-based design. “We should at least have good education in this field,” she replies. “I think every designer should get introductory classes in sustainable design methods. It's really about how we can work efficiently with materials, instead of deriving them from Earth. Looking around us and see what we already have: from scarcity to abundance. And that’s a vision that generally lacks.”

Emma states that most educational programs – on both art schools and universities – are still rather traditional. In her view, academic institutions could become more experimental. “I think this will hold the potential to stimulate innovation and makes collaborating easier. Try looking beyond yourself, and perhaps you’ll discover something that you’ve never thought of, which could literally change your life.”

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!