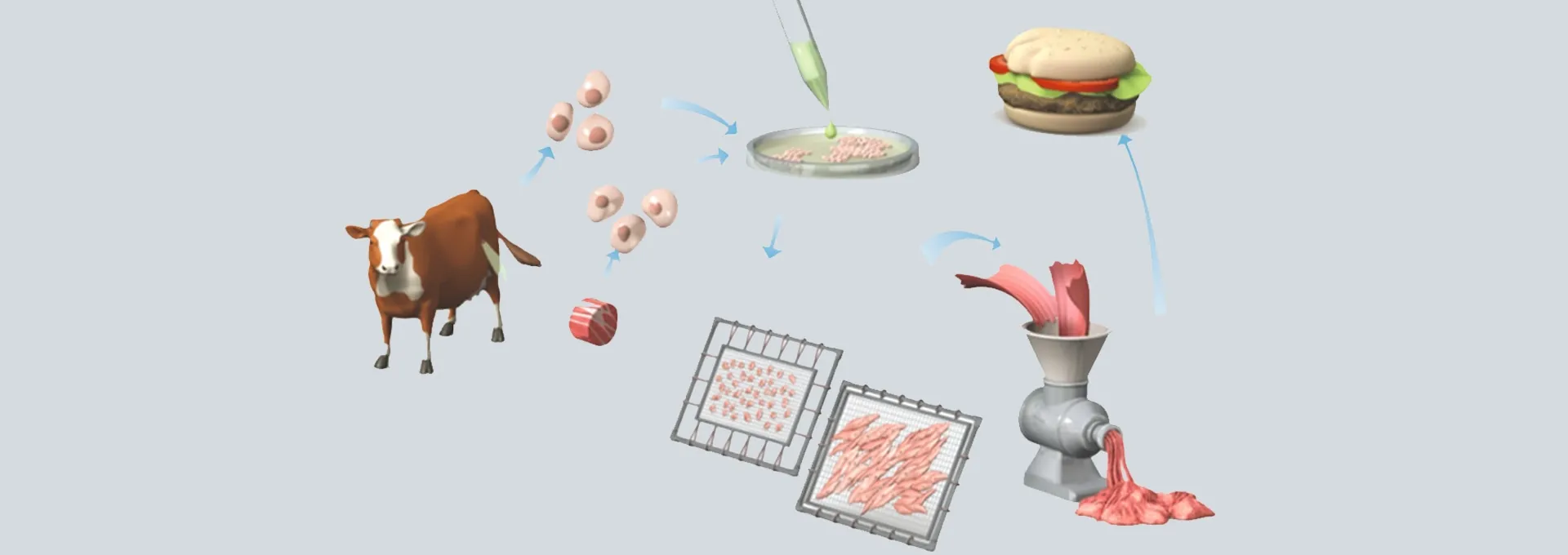

Right now, somewhere in a laboratory in California, the Netherlands or Japan, a technician is taking a few thousand skeletal muscle cells from a living animal, and placing them in an incubator in a nutrient-rich broth. The incubator will be warmed up to body temperature, causing the cells to start multiplying, doubling roughly every few days. Over the next few weeks, she will regularly replace the broth, removing cellular waste products, dead cells and restoring pH balance, similar to the way our bodies behave.

The act of hunting, cultivating and eating meat is intimately interwoven with the story of human evolution

At a certain point she’ll change the nutrient balance, causing the cells to stop dividing, and fuse together into strands of living tissue. Those strands will then be extracted, and suspended in a gel around a spongy scaffold that floods them with new nutrients and mechanically exercises them to increase their size and protein content. A month from now, the final product, consisting of billions of cells, will be ready.

87 years ago, Winston Churchill said that “we shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium.” In 2014, a team of Dutch scientists made his prediction a reality when they unveiled the first ever lab-grown hamburger for a cost of $330,000.

Today, a Bay Area startup says it can make a kilogram of beef for around $5,000, and there are at least seven other companies around the world aiming to commercialise not just lab grown beef, but chicken, duck, fish and turkey. A number of these new ‘clean meat’ companies are saying they’re going to have competitively priced products by 2020, and one of them says it will have chicken nuggets, foie gras or sausages on the market by the end of this year.

Let’s just stop, and think about that for a second.

The act of hunting, cultivating and eating meat is intimately interwoven with the story of human evolution. It’s central to so many of the key chapters: from the development of language, to the invention of fire, from the creation of agricultural societies, to the modern global livestock industry and its effects on climate change. And it has always meant the death of an animal.

Not any more.

We are now talking seriously as a species about a fundamental break from our relationship to meat within our lifetimes. That’s pretty awe-inspiring, and very, very weird.

It’s also not guaranteed. Breathless predictions from the Singularity University crowd notwithstanding, there are some massive hurdles to overcome before a consumer ready product hits the market. Biology, it turns out, is complicated. As Alex Danco (who writes the fabulous Snippets newsletter) points out, cells are much harder to work with than bits and bytes, because they strive to maintain balance. It’s difficult to get them to maintain a particular state for an extended period of time, because unlike in a steady state machine (like a computer) cells’ equilibria are constantly being pushed and pulled in every possible direction.

We are now talking seriously as a species about a fundamental break from our relationship to meat within our lifetimes

Cells are hard to grow and keep happy. Biological matter breaks down over time and most cells only make stuff for a limited period before they fail and get recycled. The usual Silicon Valley mantras don’t apply. You can’t just “move fast and break things.” The research and development requires hard science, and takes time.

However, cells have one crucial characteristic that offsets these disadvantages: they are inherently self-replicating. In Alex’s words, “imagine if your phone contained not only the hardware and software capability to run all your apps, but could also easily create brand new copies of itself through replication.” This is not magic. This is what cells are made to do. That means that in theory, a single turkey could feed an entire planet. Assuming unlimited nutrients and room to grow, a single cell can undergo 75 generations of division during three months. That means one cell could turn into enough muscle to manufacture over 20 trillion turkey nuggets.

In practice, the scale of the challenge is daunting. To grow cells industrially requires a large bioreactor — a high-tech vat that provides the perfect conditions for growth as well as movement and stimulation to exercise the cells. Currently, the largest one in existence has a volume of 25,000 litres (about one-hundredth the size of an Olympic swimming pool), which would produce enough meat to feed 10,000 people. You’d need a lot of those to create a single viable meat factory, never mind enough to start feeding entire cities or countries.

Then there’s the problem of the growth serum. Most of the nutrient broth for lab grown meat is made up of amino acids, sugars and vitamins, similar to a sports drink like Gatorade. Those ingredients are easy to synthesise artificially. A small but crucial proportion however, is made of up of animal proteins that the cells need in order to grow. Right now the primary source of that is fetal bovine serum, a byproduct of stem cells from fetuses extracted during the slaughter of pregnant cows in the dairy industry. And if that sentence just freaked you out, then you probably haven’t been paying much attention to where your cheese comes from.

In theory, a single turkey could feed an entire planet

Fetal bovine serum is expensive; a single litre costs around $600, and the industry is getting through buckets of the stuff every day. It also defeats the entire purpose, making a mockery of any cruelty-free claims. The clean meat companies are therefore going to have to figure out how to remove it from the process. Fortunately, scientists in other areas have been working on that. In other areas of biology most embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell culture is now performed serum free. All of the clean meat companies say that when they begin selling products they will have no serum whatsoever, not just for PR or environmental reasons, but because the economics make no sense.

Meat also has an incredibly complex flavour profile; because of its structure, it develops flavour at different rates as fat, muscle, and bone cook in different ways. Because the technology to recreate whole steaks doesn’t exist yet, commercial products will have to contain the right balance of fat and muscle to mimic the taste and textures of ‘real’ meat. And the closer you get, the harder it becomes.

There’s an effect in the clean meat industry known as the uncanny valley, similar to the world of CGI. The closer you get to reality, the less tolerant people become of difference. Your tastebuds and brain will give substitutes such as seitan or fake chicken plenty of leeway, but as soon as your mind switches over to going “OK this is actually meat” then even the slightest discrepancy will cause you to reject it. As animals that evolved to eat meat… we’re very good at picking up inconsistencies.

That’s why the clean meat companies are starting with products such as foie gras and chicken nuggets, which are easier to recreate. Interestingly, poultry cells grow a lot better in culture than mammalian cells, and are easier to manipulate. With mammals, you also have to take cells from younger animals, whereas with birds, a more mature animal is preferable. Case in point? Ian the chicken.

The challenges in other words, are daunting but not impossible. Given enough resources, some of these companies are going to deliver on their promises. And those resources are around: enticed by the chance of capturing a slice of the $700 billion market for global meat, venture capital is pouring in, with billions of dollars of investments in over the last few years (CB Insights has a great overview). Perhaps even more impressive than the technical accomplishments or fundraising chops of the clean meat entrepreneurs however, is their marketing savvy.

The challenges are daunting but not impossible

Mallory Locklear, a journalist from Engadget, says the leaders of these companies know the battle is going to be won and lost in the court of public taste, which means they’re going to need greater transparency and openness. They watched the agriculture industry learn some hard lessons when GMOs rolled out a generation ago. Products were placed into the food chain without checking first with the people eating them, and to many, that felt like the industry was secretively messing with us. It led to a massive public backlash that we’re still dealing with today. Food it turns out, is a pretty emotional issue for a lot of people, and it doesn’t get more emotional than meat. The clean meat pioneers are determined to get it right this time. That’s why even though their products aren’t on the market yet, we’ve been hearing about them in the news for years.

The way we treat animals is one of the worst things human beings do. The global meat industry is cruel, inhumane and disgusting. Most of the animals we eat languish in their own faeces, never set foot outdoors, and are forced to consume large quantities of antibiotics. Meat and poultry are one of the most common food sources of fatal infection, accounting for a third of global food poisoning deaths (e.g. salmonella and listeria) and modern farming practices have given rise to dangerous, drug resistant bacteria.

It’s also an ecological disaster. For every chicken you eat, imagine four thousand one litre jugs of water sitting next to it. Then imagine systematically pouring them all out, one by one. That’s how much water it takes to bring a single chicken from shell to shelf. You can save more water by skipping a single roast chicken dinner than by skipping six months of showers. Beef is even worse: it takes 2,000 litres of water to produce a single burger. Livestock feed production takes up more than a quarter of all ice free land on Earth, and it’s not helping climate change either — the keeping and eating of livestock creates more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire transport sector.

If we’re going to feed ten billion people by 2050, then humanity is going to have to cut back on its traditional meat consumption. And that’s not going to happen by asking people to become vegetarian. You don’t change things by fighting the existing reality, you build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete. You can’t change people’s minds by telling them what not to do. You give them alternatives. We’re going to have to hack the food supply with new clean, high tech, creatively engineered foods that don’t use more land, water, fertiliser or pesticides.

Forget electric cars. If you’re serious about making the world a better place, perhaps it’s time you started thinking about clean meat?

This story was republished from Future Crunch via Medium. Read the original piece here.

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

Be the first to comment!