Nature demanded that we make a choice between immortality and sex, but the Next Nature of the 21st century may not. For help, we can look back to the 20th Century, which had many storytellers playing with the parameters of the sex equals death equation. None were more successful than two young men from the Midwest who ended up here in Southern California, making their dreams in to reality which Los Angeles always promises, but rarely delivers. Walt Disney and Hugh Hefner, who seem miles apart, are in fact two sides of the same coin, flipping to decide what the Next Nature of sex and death will be.

Life itself had a choice to make early on. Would life choose unchanging immortality, or infinite mutability punctuated by death and rebirth? Though single-celled organisms are still around, life in its wisdom abandoned self-replication and embraced sex, the intertwining of individuals to produce different offspring, which adapt to their environments, and grow into their own sexual maturity to repeat the process. In other words, life would rather fuck and evolve than endure the stasis of immortality. Life traded sex for death, and we are all the better for it.

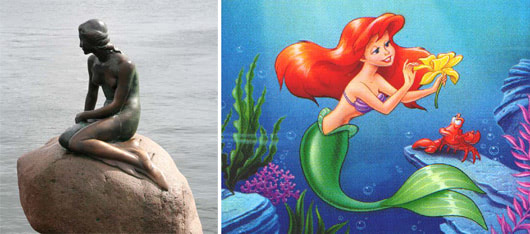

Little Mermaid statue in Denmark (left) and Disney's incarnation (right).

Little Mermaid statue in Denmark (left) and Disney's incarnation (right).

Walt Disney achieved worldwide fame because he understood that children, and the stories they were told, needed a different model in the wake of the changes in the Western culture of death. The classic fairy tales the Brothers Grimm told were for children inundated by both sex and death. Their parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, and assorted others lived close at hand, often in the same room, the muffled sounds and musky smells of sex were inescapable. So too was the presence of death. The old died with their families, friends and relatives passed young, without much or any treatment, and most importantly, children lost their brothers and sisters. They were, therefore, in need of stories to explain and contain all that sex and death. This is why Red Riding Hood is eaten in the original story, why the Little Match Girl perishes in the cold, and, why the Little Mermaid suffers for her love of the prince on legs that burn like fire and eventually dies from her enchantment, only to return to the sea as foam.

Walt Disney was born in 1901, close to those preceding centuries of misery but on the cusp of the 20th century in which death would be battled more ferociously than ever before in human history. Disney invented his most famous character, Mickey Mouse, in 1928, the very year that Sir Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin.

Disney’s fairy tales feature the off-screen deaths of many a mother, and just deserts to the villains, but they sanitize mortality. By the time of the corporate resurgence of Disney with the Little Mermaid in the 1980s, Ariel and the Prince marry and live happily ever after, an ending diametrically opposed to Hans Christian Anderson. Yet the Disney version befits a century's medical progress, the end of polio, tuberculosis, smallpox and even bubonic plague. But with the end of death, the Magic Kingdom saw no point to sex either, and banished it as well, creating the squeaky clean image that conquered the world’s children.

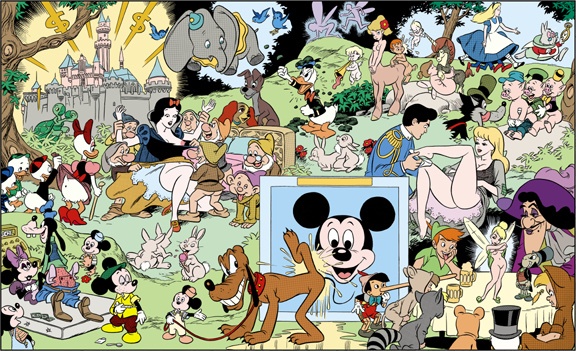

Disneyland Memorial Orgy (1967) by Wally Wood, copyright: Paul Krassner

If Walt Disney came to understand the changing nature of death and used that to build a Magic Kingdom for children and the childlike, another Midwesterner, born a generation later laid out a new set of illustrated stories for grownups.

Hugh Hefner came back to Chicago from service in the last few months of WWII poised to make his contribution as a member of the Greatest Generation. After the requisite failures — in school, in marriage, in business — he borrowed $800 dollars from his mother, raised a few thousand more from friends, and founded a magazine he called Stag Party. Before the first issue came out, another skin book called Stag threatened to sue him and Hefner changed the name to Playboy. He morphed his mascot from a deer to a rabbit, and the ubiquitous bunny was born.

Marilyn Monroe playboy shoot (left), Playboy Founder Hugh Hefner (right)

The first issue featured Marilyn Monroe, “with nothing on but the radio.” History rewards the prescient, and Playboy came out virtually simultaneously with the first successful clinical trials of the oral contraceptive pill. Hefner’s magazine became the public face of technological, mid-20th century hedonism, of sex severed from reproduction. Of course, for all its sophistication, Playboy isn’t really about sex so much as it is about masturbation. And masturbation, as the Biblical Onan reminds us, is about the spilling of seed onto infertile ground. Five decades into the so-called Playboy revolution, we find ourselves awash in an on-line pornotopia, with the now octogenarian Hef popping Viagra the way that other people take vitamins, playing out his own fantasies of sex without reproduction, sex without death.

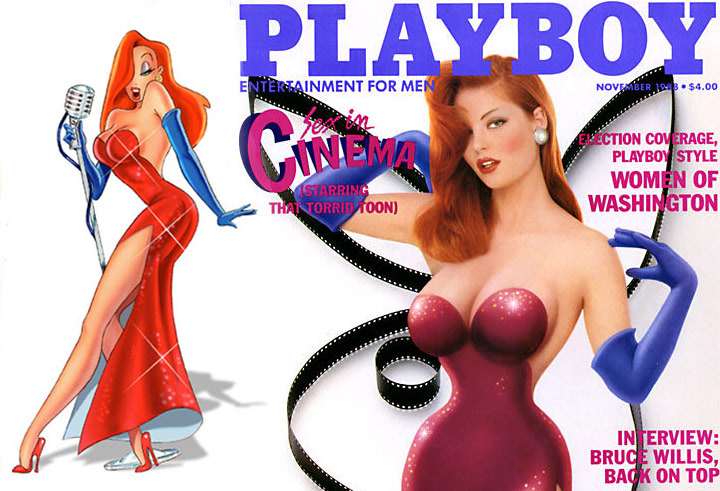

The most overtly sexual Disney Character, Jessica Rabbit: “I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way.” (Left) 1988 Playboy cover of hyperreal Jessica Rabbit (right)

So what then, do these two multi-mediated, mid-century, Midwestern megalomaniacs have teach us about Next Nature? Walt Disney sees death receding and builds a Magic Kingdom out of Princesses who don’t die, but don’t get to fuck much either. Hugh Hefner, like Disney an avid cartoonist in his youth, fills a Mansion in the Hollywood Hills with the Girls Next Door who grew up wanting to be Princesses, but he strips off their robes, and pumps up their breasts, creating a masturbatory simulation of sex without reproduction. Next Nature deserves better.

Written by Prof. Dr. Peter Lunenfeld for NextNature.net.

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!