Dit verhaal maakt deel uit van Next Generation, een serie waarin we jonge makers een platform bieden om hun werk te presenteren. Jouw werk hier? Neem contact op en bepaal je koers terwijl we samen onze toekomst verkennen.

“God schiep de Lausitz, maar de duivel legde de kolen eronder.” Een bekend gezegde in Lausitz, Duitsland. Het verwijst naar het feit dat het gebied een grote voorraad bruinkool heeft. De eerste dagbouwmijn startte in 1789, met vier nog steeds actief vandaag, die tegen 2038 gesloten moeten worden. Wat achterblijft is een postindustrieel landschap dat, in zijn materialiteit, verhalen van vernietiging vertelt. Dit verhaal wordt verteld in een installatie Post Wilderness van Melissa Schwarz, die een MA Interaction Design studeert aan de University of the Arts London (LCC). We spraken met Melissa om te bespreken hoe deze extractieve processen kunnen leiden tot een herschrijving van de natuur, een noodzakelijke stap om te kunnen oplossen wat zij beschrijft als de natuur/Natuur-kloof; om de Natuur weer natuur te laten worden.

Vertel ons over Post Wilderness.

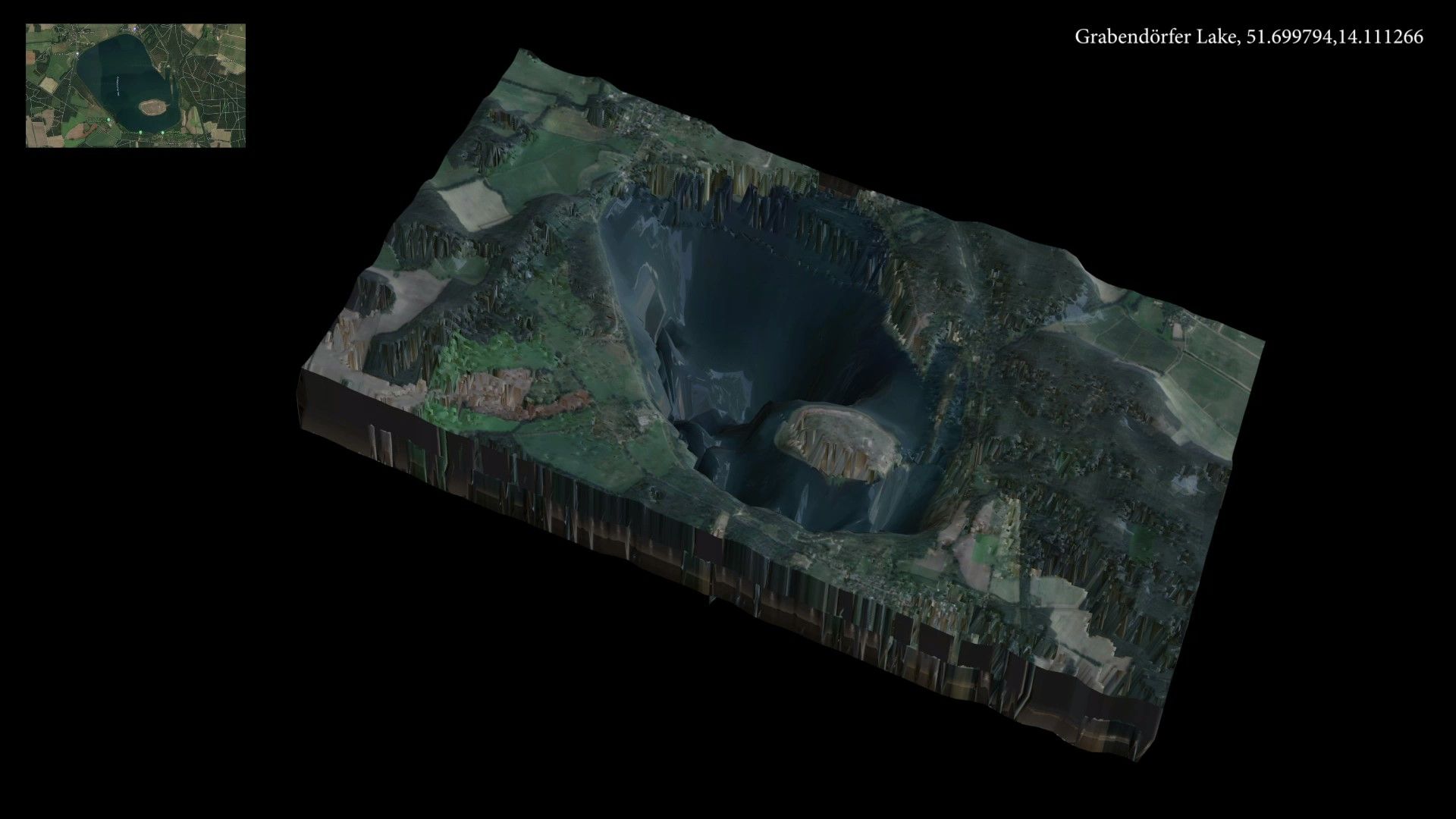

‘Post Wilderness’ is een installatie die onderzoekt wat ecosystemen vormt nadat het kapitalistische, grootschalige extractivisme hun locatie heeft verlaten en welke implicaties dit heeft in een bredere, mondiale context. Het behandelt de poëzie van mineralen uit lang vervlogen geologische tijdperken die naar de oppervlakte worden gebracht en de basis vormen voor nieuwe ecosystemen. In de poëtische vertelling reis ik door en ontdek ik dit landschap, terwijl ik nadenk over waar we nu staan, waarbij ik Lausitz gebruik als metafoor en laboratorium om na te denken over hoe we verder gaan na de kapitalistische vernietiging.

Veel landen stoppen nu met hun winningactiviteiten. Wat gebeurt er met deze plaatsen daarna?

Wat aanvankelijk mijn interesse wekte in postindustriële landschappen, waren de valse verhalen van het kapitalisme rond wat zij ‘duurzaam’ noemen, bijvoorbeeld elektrische auto's, die sterk afhankelijk zijn van de winning van bruinkool, wat ecosystemen vernietigt door grote gebieden uit te drogen en het weinige water dat overblijft te vergiftigen. Dit deed me afvragen wat er met deze plekken, deze ecosystemen, gebeurt nadat het kapitalisme de plaatsen materieel heeft uitgeput en verder is getrokken, zoals het geval is bij bruinkoolwingebieden. Hernieuwbare energiebronnen vervangen de traditionele manier om energie uit bruinkool te winnen, en veel landen stoppen nu met hun winningsinspanningen. Wat gebeurt er met deze plekken daarna? Op welke manieren worden hun ecosystemen voor altijd achtervolgd door hun extractieve verleden? Ik besloot het specifieke punt van de materiële verandering die op de locatie en het ecosysteem heeft plaatsgevonden als gevolg van extractivisme eruit te lichten. Ik vind dit een belangrijk aspect, omdat wat een ecosysteem materieel uitmaakt, de bepalende factor is voor wat erin kan bestaan. Op deze manier onthult de materiële verandering niet alleen de langetermijneffecten van extractivisme, maar laat het ons ook op een uniek zichtbare manier de schade en omvang zien die kapitalistische processen op een plek aanrichten.

Hoe verliep het creatieve proces van jouw werk?

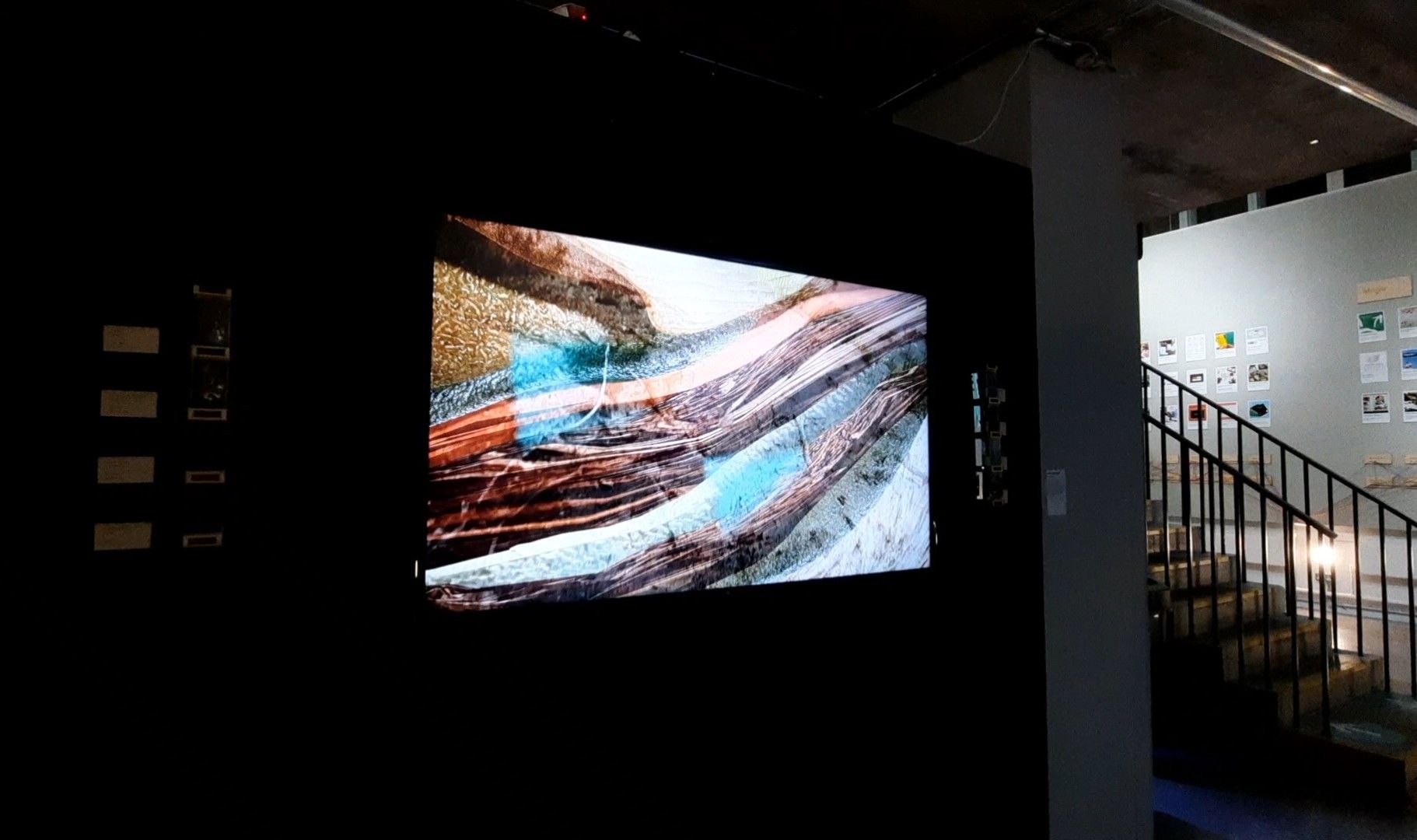

Het project is voornamelijk ontwikkeld door middel van veldonderzoek. Ik wilde dat het locatiespecifiek zou zijn, omdat ik geloof dat het belangrijk is om directe effecten te laten zien. Om dit te bereiken, koos ik voor Lausitz in Oost-Duitsland en reisde ik daarheen om mijn onderzoek uit te voeren, video- en audiomateriaal te verzamelen en bodemmonsters te nemen voor mijn installatie. Om de punten die ik maak te verbinden met wat er wereldwijd gebeurt, heb ik ook veldwerk in Londen gedaan. Het resultaat was een op een scherm gebaseerde installatie, die ook objecten incorporeerde. Deze objecten waren twee zuilen aan weerszijden van het scherm, die gemaakt waren van hars waarin materiaalmonsters zaten die ik had genomen uit de specifieke ecosystemen. Haraway's ‘Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene’ als tekst had een grote invloed op hoe ik mijn verhaal voor de film heb opgebouwd, omdat zij specifiek ingaat op verhalen vertellen. “…Ik zoek naar echte verhalen die ook speculatieve fabulaties en speculatieve realismen zijn. Dit zijn verhalen waarin spelers uit verschillende soorten, die verweven zijn in gedeeltelijke en gebrekkige vertalingen over verschillen heen, manieren van leven en sterven opnieuw uitvinden die afgestemd zijn op nog steeds mogelijk eindige bloei, nog steeds mogelijke herstel” (Haraway, 2016, p. 10). Het verhaal van Lausitz is zo'n verhaal. Ik ben mijn script daarom als een ‘vertaling’ in die zin gaan benaderen, wat ik zag als een oefening in het communiceren van niet alleen de trieste realiteit van de vernietiging van de biosfeer die heeft plaatsgevonden, maar ook om een hoopvol verhaal te vertellen, aangezien dit het uitgangspunt is van waaruit we de toekomst tegemoet gaan.

Het is misschien niet de natuur die er oorspronkelijk bestond, maar het is een nieuwe natuur, die eveneens waardevol is en een stap in de juiste richting naar de toekomst van de natuur.

Wat onthult het postindustriële landschap over mensen en de natuur?

Postindustriële landschappen onthullen het humanistische beeld van natuur en cultuur als gescheiden te beschouwen. Dit heeft het mogelijk gemaakt dat het milieu op de manier waarop het is gebeurd, is uitgebuit en vernietigd. Het is precies de reden waarom de Lausitz vol ligt met uitgestrekte verwoestingen; extractivisme dat bossen verandert in maanlandschappen en meren onbewoonbaar maakt; want de natuur werd en wordt nog steeds gezien als een middel voor menselijke doeleinden. Het laat echter ook zien dat we in staat zijn om het beter te doen; in de Lausitz hebben herbebossings- en rewilding-inspanningen, die deels eeuwen geleden zijn begonnen, ervoor gezorgd dat een groot deel van het gebied bedekt is met wat voor het onoplettende oog er niet anders uitziet. Ik maakte wandelingen in grote bossen daar, om pas na enige tijd op te merken dat de bomen in te rechte lijnen stonden om natuurlijk voor te komen. Ik klom naar een uitkijkpunt om een groot, rustig meer beneden te zien, om vervolgens van een bord te vernemen dat dit meer slechts veertien jaar oud is en is ontstaan door het afdammen van een krater die achtergelaten was door graafmachines. Het is misschien niet de natuur die er oorspronkelijk was, maar het is een nieuwe natuur, die eveneens waardevol is en een stap in de goede richting voor de toekomst van de natuur.

Kun je ons vertellen wat je bedoelt met ‘Natuur wordt weer natuur’?

Vaak hoort of leest men uitdrukkingen zoals “we moeten terug naar de natuur”; wat een begrip van de natuur vandaag onthult als een bleke afspiegeling van wat ze ooit was, waarbij het begin van het einde van de “echte” natuur ergens in het verleden ligt (Law & Lien, 2018, p. 143). Dit onthult voor mij het ontologische probleem dat het concept natuur heeft. Ik noemde dit ontologische probleem de Natuur/natuur-scheiding. Jonathan Moore schrijft dat de natuur/cultuur-scheiding ervoor zorgde dat natuur, Natuur werd, wat hij definieert als omgevingen zonder mensen (2016, p. 87). Dit wordt ook weerspiegeld in een begrip van natuur als “de ander” die menselijke doelen dient. Ik geloof dat Natuur in deze zin nooit heeft bestaan sinds er mensen zijn; en ik denk daarom dat Natuur weer natuur zou moeten worden, zodat wij als mensen verantwoordelijkheid kunnen nemen met het besef dat Natuur; een onaangeroerde wildernis, niets is waarnaar we zouden kunnen of moeten streven terug te keren. Deze ontologie van natuur maakt het vrij om op een betere manier verandering te bewerkstelligen.

Wat onthult de vergelijking tussen Lausitz en Londen?

Hoewel de effecten van extractivisme misschien duidelijker zijn op plaatsen zoals Lausitz, zijn de effecten wereldwijd zichtbaar. Daarom was het doel van mijn werkstuk om over te brengen dat een drijvende factor van ongezonde of stervende ecosystemen verband houdt met extractivisme. Extractivisme en de resulterende materialiteit van een plaats zijn daarom een lens geworden voor mijn werkstuk waardoor ik het publiek wilde laten kijken naar hun eigen omgeving. Extractivisme en de ecopolitiek van materie worden vaak alleen besproken in het kader van vervuiling, en het is zeker onderdeel van het gesprek dat ik met mijn werk wil uitlokken, maar ik wil ook iets dieper ingaan. De vraag waarom een stuk metaal in de rivier de Theems drijft, is nauw verbonden met de vraag waarom de bomen in de meeste bossen in Lausitz in perfecte rijen staan. Hoewel dit geen voor de hand liggende connectie is, is het er een die het waard is om te maken om geopolitieke processen beter te begrijpen en hoe deze verbonden zijn met geglobaliseerd kapitalisme.

Postindustriële landschappen kunnen ons leren hoe we kunnen werken aan duurzaamheid door ons te laten zien welke mogelijkheden er zijn nadat het kapitalisme een plek materieel heeft uitgeput en is verder getrokken.

Hoe helpt jouw project de toekomsten van de natuur te verkennen?

Ik geloof dat postindustriële landschappen unieke ruimtes openen, zowel letterlijk als figuurlijk. Ruimtes die laboratoria kunnen zijn waarin een posthuman subject verantwoordelijkheid kan uitoefenen in wereldvormende praktijken. Ze kunnen laboratoria zijn in methodologische zin, waardoor we kunnen nadenken over ontologieën voor de natuur en over haar toekomsten. Postindustriële landschappen kunnen ons leren hoe we kunnen werken aan duurzaamheid door ons te laten zien welke mogelijkheden er zijn nadat het kapitalisme een plaats materieel heeft uitgeput en is verdergetrokken. Met ‘Post Wilderness’ onderzoek en construeer ik de ruimtelijke verhalen van een plek die op unieke wijze zowel het verleden als de toekomst van de natuur combineert. Nieuwe ecosystemen groeien op de grond van de vernietiging van de oude. En ik geloof dat een verkenning van dergelijke ruimtes een nuttig hulpmiddel kan zijn om bevrijd te worden van de last om gevangen te zitten tussen toekomstige en vroegere natuur, en ruimte maakt voor de acceptatie van de natuur nu, zonder te hoeven differentiëren tussen concepten van natuur, post- of pre-industrieel, pre- of posthuman, wat ik geloof een nuttiger hulpmiddel te zijn om te werken aan een herschrijving van de menselijke geschiedenis, zoals het kritisch posthumanisme bepleit.

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!