Aan het einde van elke koude winter is er een debat in Nederland over de vraag of de boswachterij de ossen, paarden en herten die grazen in de Nederlandse natuurgebieden moet voeren. Het officiële beleid van de Nederlandse boswachterij is om het ecosysteem zichzelf te laten beheren, wat ertoe leidt dat de zwakkere dieren – 24% van de populatie – omkomen door gebrek aan voedsel: een te natuurlijk schouwspel voor de meeste ‘natuurliefhebbers’.

Aan het einde van elke koude winter is er een debat in Nederland over de vraag of de boswachterij de ossen, paarden en herten die grazen in de Nederlandse natuurgebieden moet voeren. Het officiële beleid van de Nederlandse boswachterij is om het ecosysteem zichzelf te laten beheren, wat ertoe leidt dat de zwakkere dieren – 24% van de populatie – omkomen door gebrek aan voedsel: een te natuurlijk schouwspel voor de meeste ‘natuurliefhebbers’.

Als reactie op de protesten betogen de initiatiefnemers van het Nederlandse ‘handen-af’ landschapsbeheer dat de protesten van wandelaars, fietsers en andere toeristen slechts illustreren hoe vervreemd mensen zijn geraakt van de natuur. Maar zijn de uitgangspunten van deze beleidsmakers echt geldig? Is het verdedigbaar om de dieren aan de elementen over te laten of is dit spel uit de hand gelopen?

Het recreëren van een prehistorisch landschap

Sinds de afgelopen decennia is het beleid voor natuurgebieden in Nederland gericht op het herstellen van het oorspronkelijke landschap, zoals dat bestond in de prehistorie. In de praktijk betekent dit dat land wordt gewonnen op de zee of wordt gekocht van boeren en wordt omgevormd tot het landschap waarvan wij denken dat het 8.000 jaar geleden bestond, lang voordat de mens zijn stempel erop drukte.

Recreatie in de Oostvaardersplassen in Nederland

Hoewel dit beleid redelijk succesvol is geweest en heeft geresulteerd in enkele prachtige, grotendeels zelfvoorzienende gebieden, zijn er ook nadelen. Een probleem is dat we niet precies weten hoe het landschap er in de prehistorie uitzag en veel goed onderbouwde gissingen moeten doen. Een ander probleem dat direct opkwam met de wens om een oud ecosysteem te herstellen, is het feit dat sommige elementen simpelweg niet meer bestaan.

Een probleem is dat we niet precies weten hoe het landschap er in de prehistorie uitzag

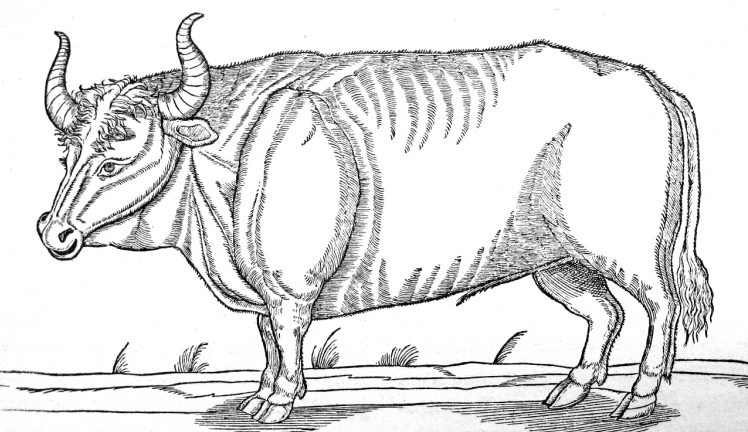

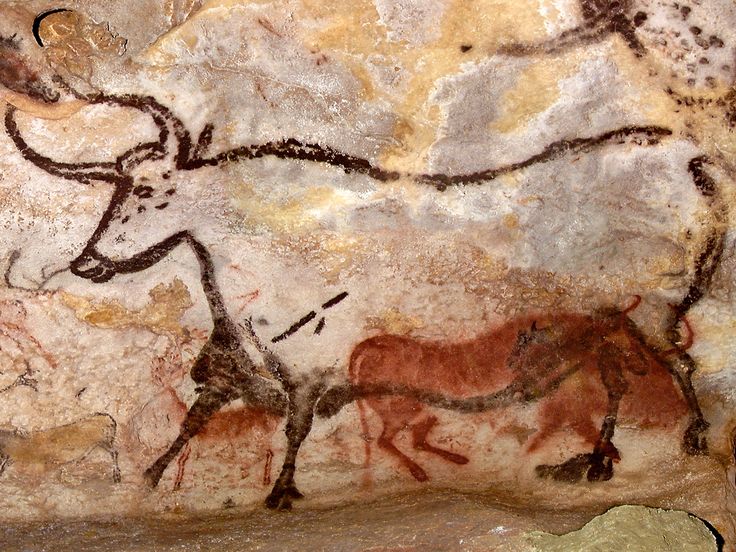

Bijvoorbeeld de voorouder van het gedomesticeerde rund, de oeros (Bos primigenius), een soort enorm wild rund dat in de prehistorie Europa, Azië en Noord-Afrika bewoonde, stierf uit in 1627. De oeros was veel groter dan de meeste moderne gedomesticeerde runderen met een schouderhoogte van 2 meter en een gewicht van 1.000 kilogram. Domesticatie vond op verschillende plaatsen in de wereld ongeveer tegelijkertijd plaats, ongeveer 8.000 jaar geleden. De oeros verscheen al in Europese grotschilderingen uit het Paleolithicum – zoals die gevonden zijn in Lascaux en Livernon in Frankrijk – en werd beschouwd als een uitdagend prooidier.

De belangrijkste oorzaken van het uitsterven van de oorspronkelijke oerossenpopulatie waren jacht, een verkleining van het leefgebied door de ontwikkeling van de landbouw, klimaatveranderingen en ziekten overgedragen door gedomesticeerde runderen, die zo verschillend zijn in grootte en bouw dat ze als aparte soorten worden beschouwd. De laatste geregistreerde levende oeros stierf in 1627 in het Jaktorów-woud in Polen aan natuurlijke oorzaken.

Het terugfokken van de uitgestorven oeros

In 1920, ongeveer 300 jaar nadat de oeros was uitgestorven, probeerden de gebroeders Heck, twee Duitse biologen en dierentuin directeuren, oerossen te recreëren die zij kenden van de talloze bestaande tekeningen en schilderijen. Hun idee was dat het genetische materiaal van de oeros nog steeds verspreid aanwezig was bij verschillende gedomesticeerde dieren en dat het mogelijk zou zijn om de oorspronkelijke uitgestorven oeros terug te fokken.

Oerossen afgebeeld in oude grotschilderingen in Lascaux.

Oerossen afgebeeld in oude grotschilderingen in Lascaux.

De resulterende dieren, Heck-runderen of gereconstrueerde oerossen genoemd, lijken op de oorspronkelijke oeros in hun vermogen om autonoom te leven, zij het zonder hun indrukwekkende grootte. Ze tellen tegenwoordig duizenden in Europa, maar vanwege hun intolerantie voor mensen in hun omgeving zijn geregenereerde oerossen minder geschikt voor natuurgebieden die open zijn voor het publiek. Op deze locaties fungeert het minder agressieve Schotse Hooglandrund als vervanger voor de uitgestorven oeros.

Tegenwoordig lijken de Schotse Hooglandrunderen op talloze plaatsen in het Nederlandse landschap net zo sterk en onafhankelijk als de oorspronkelijke oeros – bijna als volleerde acteurs –, maar de feiten blijven dat, in tegenstelling tot de prehistorische oeros, het Schotse Hooglandrund een gedomesticeerd dier is, afhankelijk van mensen. Terwijl in hun oorspronkelijke omgeving in Schotland de Hooglandrunderen in de winter naar de valleien werden gebracht waar ze enige beschutting konden vinden in de schuren van boeren, is er in het geregenereerde prehistorische landschap geen plaats voor dergelijke niet-prehistorische schuilplaatsen.

Tegenwoordig wonen er meer dan 16 miljoen mensen in Nederland, wat de bewegingsvrijheid van de dieren aanzienlijk beperkt om een geschikt leefgebied te vinden.

Een ander verschil met de prehistorische oeros en hun hedendaagse vervangers is het enorme verschil in hun leefomgeving. In de prehistorie woonden er misschien een paar honderd mensen in een gebied ter grootte van Nederland, tegenwoordig zijn dat er meer dan 16 miljoen, wat de bewegingsvrijheid van de dieren aanzienlijk beperkt om een geschikt leefgebied te vinden. Mogelijkerwijs zou de oorspronkelijke oeros nooit hebben gekozen voor het omheinde leefgebied waarin hun vervangers momenteel terechtkomen. De afwezigheid van roofdieren, zoals wolven, draagt alleen maar bij aan de tragedie.

Geregenereerde natuur of recreatieve simulatie?

De kernvraag van het debat zou moeten draaien om de vraag of we deze zogenaamde natuurreservaten en de levende dieren die erin leven, moeten beschouwen als een echt natuurlijke omgeving, of dat we ze beter kunnen zien als recreatieve simulaties van een prehistorisch landschap, gemaakt voor het plezier en de educatie van mensen. Gezien de moeilijkheid (lees: onmogelijkheid) om de prehistorische ecologie en haar bewoners volledig te recreëren in zo'n relatief klein gebied dat al overvol is met mensen, neigt men naar het laatste antwoord.

Net zoals de landschapsschilderijen die mensen ophangen boven hun banken voor hun plezier, zijn deze geregenereerde natuurgebieden slechts kopieën van een oude natuur die lang verdwenen is en nooit echt kan worden hersteld: verandering gebeurt, evolutie gaat door. Het beste wat we kunnen doen is een heropvoering – een simulatie van het landschap waarvan we geloven dat het in de prehistorie bestond – en hoewel het realisme van deze simulatie zeker diepgaander is dan in elk willekeurig landschapsschilderij, zal het uiteindelijk altijd een afgeleide blijven.

Deze geregenereerde natuurgebieden zijn slechts kopieën van een oude natuur die lang verdwenen is en nooit echt kan worden hersteld

Nu moet je het niet verkeerd begrijpen: De Nederlandse pogingen om prehistorische landschappen te recreëren zijn niet per se slecht beleid. Het zijn vormen van cultureel erfgoed die mensen niet alleen onderwijzen over de geschiedenis van de regio, maar ook voorzien in de behoefte aan groene zones in een overmatig verstedelijkt gebied – wat niet alleen ten goede komt aan mensen, maar ook aan wilde vogels die dankbaar de winter doorbrengen in de groene zones.

Al met al kunnen de geregenereerde prehistorische landschappen van Nederland het best worden begrepen als theater: een poging om het lang verdwenen historische landschap en zijn acteurs te recreëren binnen een hedendaags toneel. Net zoals in een toneelstuk of een film, zijn we bereid onze ongelovigheid opzij te zetten en ons onder te dompelen in het denkbeeldige verhaal dat voor ons wordt opgevoerd.

Niettemin moet een theaterregisseur ook zorgvuldig overwegen wat de acteurs moeten doorstaan voor het goede verloop van een toneelstuk. In dit opzicht zijn de afschuwelijke en pijnlijke sterfgevallen van de verhongerende Schotse Hooglandrunderen en Heck-oerossen een vorm van ‘method acting’ die misschien een beetje te ver is doorgevoerd.

Comments (0)

Share your thoughts and join the technology debate!

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!